Before even heading towards a potential solution to the problems faced by companies when they use artificial intelligence, let’s take the time to analyze the current context. Starting with an estimate that is enough to make any entrepreneur salivate: The long-term AI opportunity in added productivity growth is estimated at $4.4 trillion (according to a study by McKinsey). The cake to be shared is huge, but the number of companies wishing to take a piece (the biggest possible, obviously) is just as large. So for obvious reasons, business leaders, and probably all of us, are making a dangerous trade-off. We are swapping causality for correlation. We are trading the ability to understand why something happened for a statistical probability that it might happen again.

For decades, we have used software that was perfectly logical. If someone saw themselves refused credit or a job by software, any competent person could analyze the code and determine which specific rule triggered that decision. These simple and predictable rules have been replaced by black box models coming with millions of parameters, interactions of interactions that are mathematically deterministic but semantically indecipherable. This leads to the introduction of a profound operational vulnerability: Epistemic Uncertainty.

If the AI model we use gives us a “good” answer, we have no way of knowing if the reasons that motivated this answer are the “right” ones. For example, I could receive a recommendation to buy a stock, and realize that it was a good idea. But was this recommendation made to me because the AI performed a meticulous analysis of market fundamentals (good reason)? Or because it noticed that this stock rose only during sunny months, and it is currently sunny (spurious pattern)? In the first case, I could eventually reproduce the experience with success. In the second, I am certain to face failure. In any case, I have no certainty since I cannot understand and analyze the model’s reasoning.

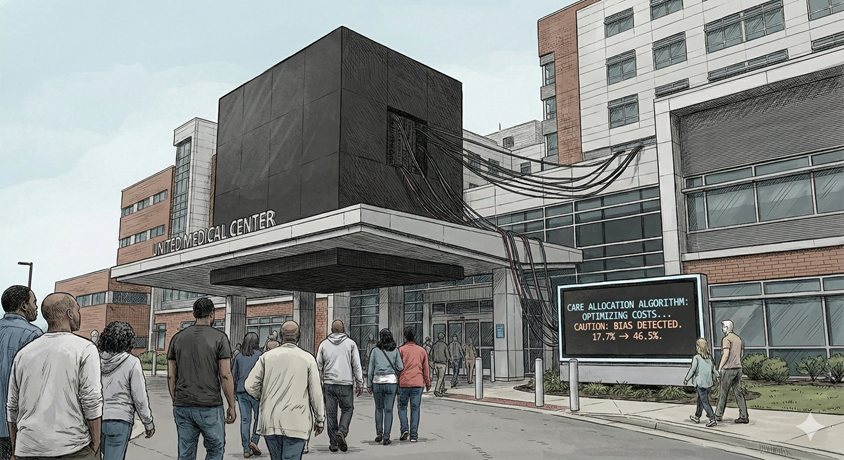

When “why” is a question of life or death

A perfect example to explain the danger when it comes to trusting a black box occurred in 2019 in the medical field in the United States. In an article published by the journal Science, we learn that an algorithm whose functioning was perfectly opaque was tasked with helping allocate care management resources to 200 million patients in American hospitals. Its role was simply to predict which patients would require the highest care costs in the future. The calculation was done based on a logic of solid appearance: sicker people cost more. In reality, African-American patients historically generate lower costs than white patients for the same level of illness, due to a lack of equal access to care.

By following its logic, the Black Box therefore made a simple deduction regarding the African-American population: Lower cost = Better health. Consequently, many Black patients saw themselves refused additional care (exceeding the usual budget) even though they were just as sick as white patients for whom this care was granted. It took years for this problem to be identified and for a fix to be applied, making the percentage of Black patients receiving additional help jump from 17.7 to 46.5%.

This textbook case highlights the insidious nature of the danger. The algorithm did not make a mistake in the mathematical sense, even going so far as to perfectly optimize the function it was given: predicting costs. The problem residing in the very construction of this Black Box. Any doctor who could have read in the code the rule “If low cost then good health,” it would have been corrected immediately.

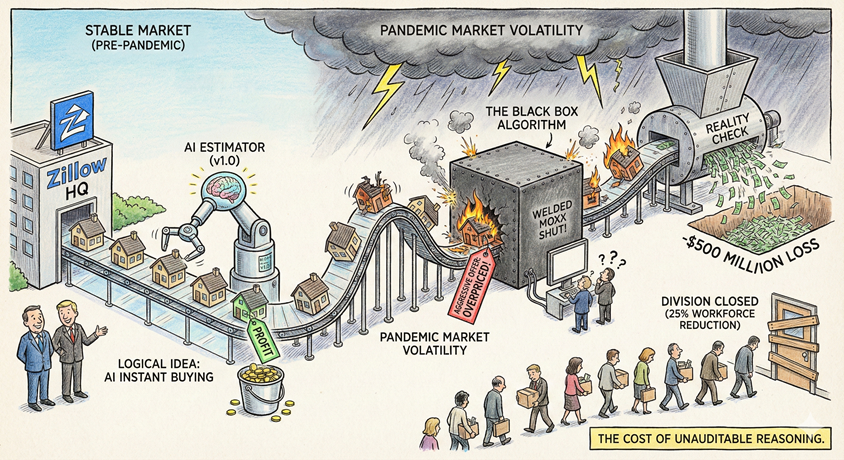

The 500 million dollar crash: When AI doesn’t see the wall coming

Zillow is another textbook case which this time does not touch on health, but on shareholders’ wallets. Once again, everything starts from a logical idea for this American real estate giant. Use an AI to precisely estimate the value of a house, buy it, lightly renovate it, and resell it with profit. Everything worked perfectly as long as the real estate market remained stable. But as soon as the market became volatile during the pandemic, the algorithm started to derail.

The problem? The AI was not built to face brutal changes in trends. They continued to make aggressive purchase offers based on historical correlations that had lost all validity. And because the model was opaque, the company’s executives had no way to determine if the algorithm was adopting a bold strategy or simply making a calculation error.

The result? In November 2021, Zillow was forced to close the division using the algorithm, leading to the layoff of 25% of its workforce and a loss of more than 500 million dollars. In short, the inability to audit the AI’s reasoning in real time turned a tool for profit into a money-losing machine.

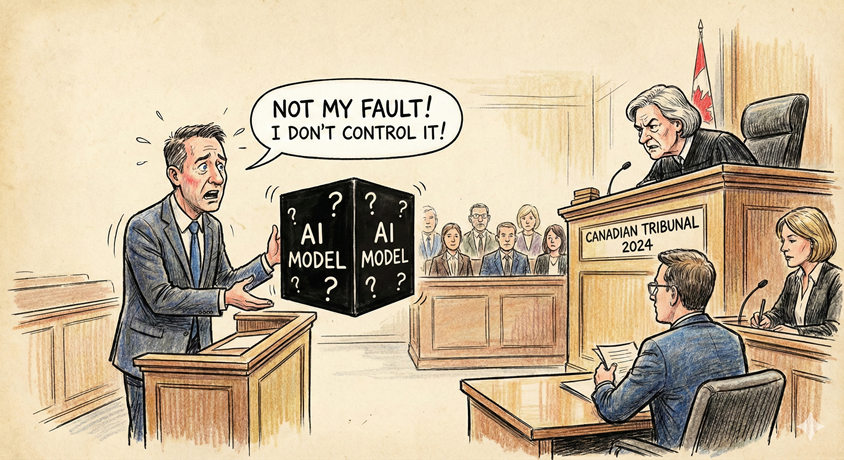

“It’s not us, it’s the bot”: The illusion of legal irresponsibility

If I don’t control the black box AI model that my company uses, I am not responsible for its errors, right? Right…??? This is probably what Air Canada told itself in 2022 after refusing a refund to one of its passengers. This person, in mourning, had used Air Canada’s chatbot to ask if it was possible for him to benefit from a reduced fare on his plane ticket due to the death of a relative. The chatbot then hurried to affirm that this was indeed the case, even indicating to him the procedure to follow to obtain this reduction. When the time came to claim it, Air Canada refused. Before the court, the airline tried to describe its chatbot as a “distinct legal entity.” I let you imagine the rest: In 2024 the Canadian tribunal categorically ruled that a company is responsible for all information communicated on its site, whether written by a human or generated by a black box.

To put it simply, even if you cannot control or explain what your AI generates, you are still responsible for the damage it causes. The opacity of a model is not a defense argument.

Knowing when to stop before you no longer understand

We are at a tipping point. Various regulations, like the EU AI Act, and the courts are starting to demand not just performance anymore, but justification.

The risk for companies in 2026 is no longer “missing the AI train,” but boarding a high-speed train with tinted windows and where the controls have been lost. Before deploying a “Black Box” model because it is 1% more accurate than a transparent model, every leader should ask themselves the question: “If this machine takes a decision that sinks my company or hurts a customer, will I be able to explain to the judge why?”

If the answer is no, then the cost of opacity is probably already higher than the expected productivity gain.